Do you dream of riding an elephant on your Southeast Asia vacation? Have you always wanted to get close to one of these noble beasts, outside of a zoo setting? Do you just want to see cute baby elephants do tricks? According to some experts, you shouldn't. Especially in Cambodia.

Asian elephants are compelling beasts, but they are often sorely mistreated in the tourism industry. The training that's required to make them safe around people is often akin to torture, as demonstrated by the traditional Thai "phajaan" or "crush," where young animals spirits are systematically broken through torture and social isolation. And don't be fooled when attractions swear up and down that they use humane training techniques: when incomes are on the line, humane, slow-moving training techniques often go out the window.

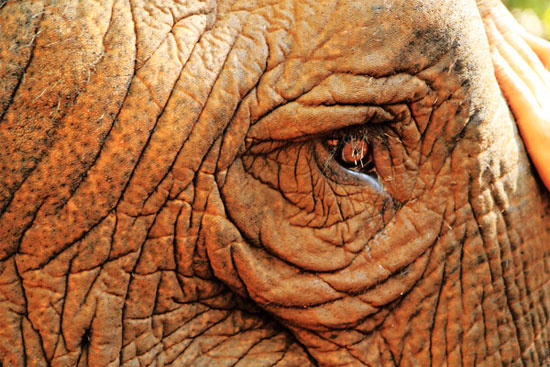

Elephant outside Sen Monorom in Mondulkiri, Cambodia.

Health is another major issues for tourism industry elephants in Southeast Asia, who are often overworked, underfed and beaten if they fail to perform properly. This combination of poor care and equally poor treatment often makes these intelligent, sensitive animals go off the deep end: repetitive swaying and nervous tics are trademark behaviours of depressed elephants -- as well as occasional violent outbursts.

All these considerations don't seem to carry much weight in the Southeast Asian tourist scene, where elephant attractions are both popular and profitable, cashing in on visitors' romantic ideas of an exotic Southeast Asia holiday. Thankfully, there are ways to get up close and personal with elephants in Southeast Asia without contributing to animal cruelty.

The Elephant Valley Project, an elephant sanctuary located in the northeastern Cambodian province of Mondulkiri, is run by the energetic Jack Highwood, who started his charity in 2006, and the Elephant Valley Program in 2007. The Mondulkiri facility now has 12 rescued elephants, obtained from locals. Owners will often will accompany the elephant to the sanctuary as its personal "mahout," or handler.

Gentle giants.

The Bunong people of Mondulkiri, an indigenous minority within Cambodia, traditionally captured young elephants from the wild. The elephants would help them log, clear brush and travel for long distances through the jungle. But a wild elephant hasn't been captured in Mondulkiri in 22 years, and much ancient knowledge about elephant care was lost with the Khmer Rouge war years. Now, the few remaining Bunong elephants are used more often in tourist attractions than they are for logging or brush clearing.

Cambodia -- and Mondulkiri, where the bulk of elephant riding in the country takes place -- is an especially dodgy proposition for aspirant elephant riders in Southeast Asia. That's because unlike Thailand and Laos, Cambodia just doesn't have very many elephants -- Highwood says there are 54 domestic elephants left in Mondulkiri, with 14 of those elephants working." It doesn't make sense to ride those last 14 into the ground," Highwood says. Recent studies (PDF) indicate that the Cambodian Asian elephant population is likely between 250 and 600."

It's a different situation in Thailand, Highwood said, where a large number of "unemployed elephants" with nowhere to go as Thailand's forests have been hacked down. "You can go to Thailand and see a trek camp with 40 or 50 elephants -- you can have a replacement," Highwood says, noting that the Thai camps are able to at least give the animals the occasional break. But with so few in Mondulkiri, he says, you can't replace one. "The family needs income," he says.

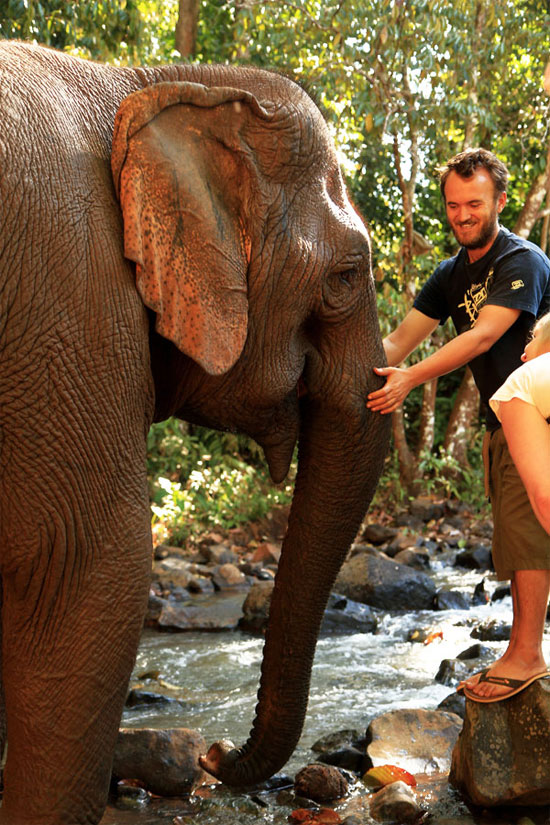

Highwood says that elephant riding is rarely the profound experience tourists expect. Elephant riding is not on offer at his sanctuary; Elephant Valley instead gives visitors a chance to touch, wash and get close to his rescued charges.

"A lot of Western tourists go on an elephant ride and say, Wow, that was horrible. The elephant looked terrible. We ate some food and came back,' " Highwood says. What tourism offers, he adds, is the chance to get people to think.

Long time Mondulkiri resident and actively-retired development worker Bill Herod, who has worked for many years with the Bunong, agrees with Highwood's assessment. "Riding elephants may be a great photo-op, but it isn't much fun. It is uncomfortable and there isn't much to see. Sitting 12 feet up in the air and having your face lashed by tree branches, you can't see much of the elephant or your surroundings."

Get up close, but no need to ride.

In Mondulkiri, Herod adds, the Bunong people aren't seeing much in the way of profits from elephant riding either. Much of the money paid for elephant riding goes to the business interests that make the arrangement, such as guesthouses, travel operators and guides, rather than to the person who owns and cares for the elephant or to the Bunong villagers. "If you care about elephants, don't get taken for a ride," he advises.

WHAT ABOUT THE LOCALS?

Poor Southeast Asians need to make an income, and elephants are a great way for locals to make money from tourism. That's a very important consideration, and it falls to outside organisations to convince elephant attraction operators and elephant owners that they can treat animals more kindly without taking too big a financial hit.

Highwood's efforts to convince locals to keep some forest land for sanctuary elephants includes providing free medical care for three nearby villages. Elephant owners and landowners willing to rent to the sanctuary are paid in rice, as much as they would get from farming.

"The idea behind this than is they see a value in the forest, income from the forest, worth," said Highwood. "Otherwise, they don't see any jobs coming from the forest, just wasteland."

WHAT IF I WANT TO RIDE AN ELEPHANT ANYWAY?

If you are deadset on riding an elephant, here are a few ways for amateurs to determine if an animal is well-treated or not - and if a elephant programme is worth your time and money.

Before you patronise any kind of attraction or tour featuring elephants, do some research first. Check their website, if they have one, and see what customer reviews on travel websites have to say about the establishment. The project's emphasis should be focused on rescuing and taking care of both elephants and the local community, not on serving tourists -- although responsible tourist programmes are great too.

Once there, check the animal. Can you see the animal's ribs? Can you see dips behind the hipbone? According to Highwood, elephants typically eat for 15 to 20 hours a day, but are often fed too little in captivity. "Families don't feed them, assuming they can get enough in the forest or paddock," he says.

Check for signs of dehydration, too. "If the toenails are pulled back, cracking or peeling, [the elephant is] really dehydrated," says Highwood. "They don't have time in the river, and probably don't drink enough."

An Elephant Valley resident.

Is the animal limping, or favouring one foot over the other? Does the animal have visible scar tissue? Can you see abscesses, wounds, or weeping sores?

Observe the animal's behaviour, too. Is the elephant swaying, or biting its own trunk? These are signs it is in pain, or nervous. Tired elephants will look listless, and will sometime rest their trunk on the ground.

Circus acts, "tricks," or many elephant rides a day are bad signs. Reputable sanctuaries and trekking operations usually won't offer these attractions.

Consider community buy-in. Is the programme making an effort to reach out to the community in some way?

More information

The Elephant Valley Project

We paid US$30 for a half day trip which included transport and lunch.

World Elephant Day

Story by Faine Greenwood

Faine is a DC and Southeast Asia based journalist/geek/blogger - check out Faine's website at http://fainegreenwood.com/.